Hackathon at Northern Research Station Edinburgh - Day 1

📷 Group Photo by Mahmoud Elmokadem

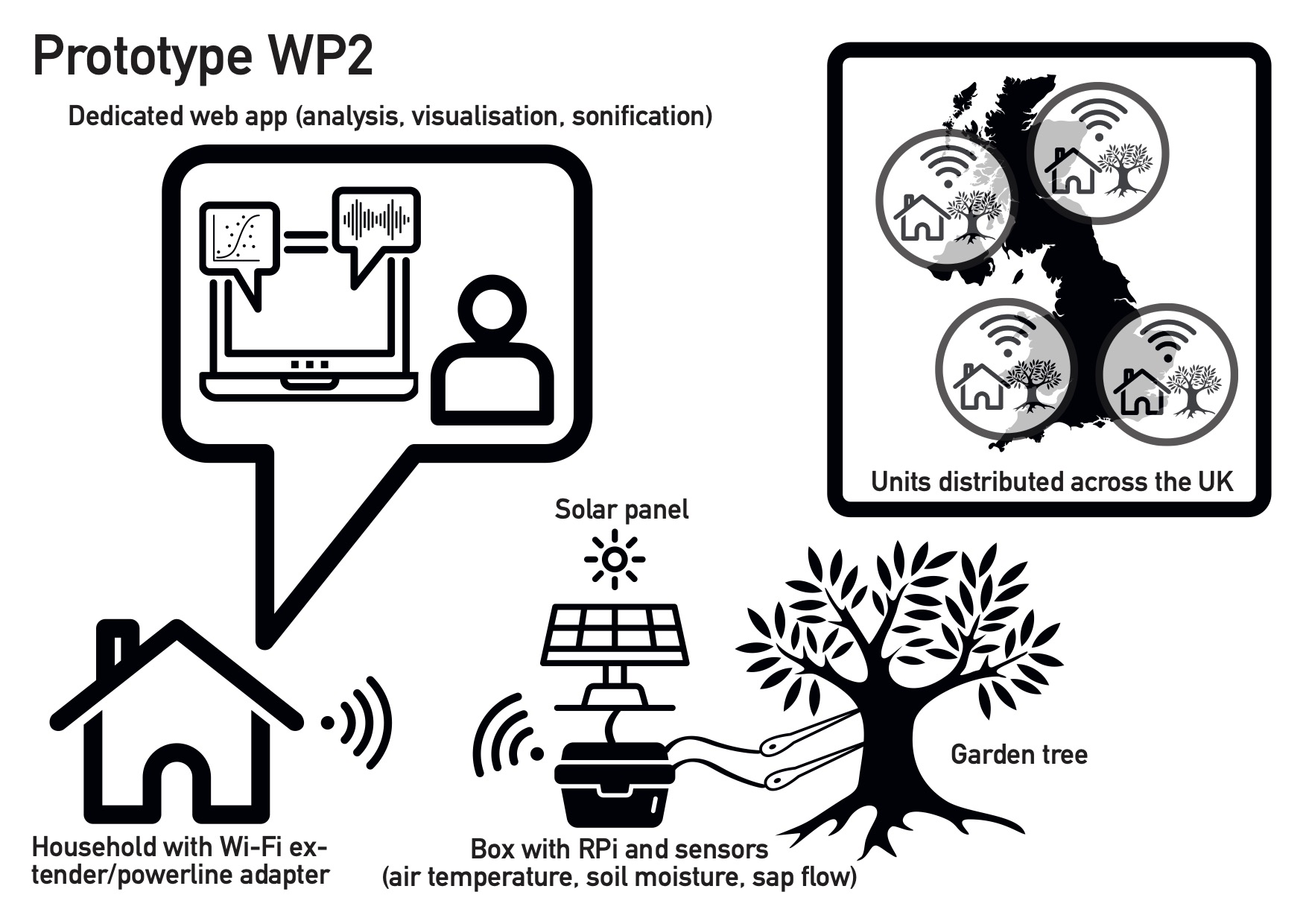

We met for the first day of our 2-day Sensing the Forest hackathon at the Forest Research Northern Research Station in Edinburgh to develop a new prototype, which is one of the main contributions of Work Package 2 (WP2). The objective of WP2 is to develop an in-house Internet of Things (IoT) prototype to measure variables related to tree stress, such as sap flow, air temperature, humidity and soil moisture to be piloted using community/citizen science methodologies connected to web applications for data analysis, visualisation and sonification. Figure 1 shows a diagram of our vision.

Hackathon contributors

The hackathon contributors are:

- George Xenakis (lead of WP2’s vision)

- Luigi Marino (QMUL)

- Mahmoud B. Elmokadem (DMU)

- Subhash Arockiadoss (DMU)

- Ning Liu (QMUL)

- Stanley Raymond Parker (QMUL)

- Krishna Nama Manjunatha (DMU) (online)

- Ireti Olowe (UAL) (online)

- Anna Xambó (QMUL)

Aim of day 1

The aim of day 1 has been to create a think-tank space and bring together our different disciplines, related projects and early prototypes to the table. The day started with a provocative keynote speech by Ireti Olowe about ideas on mappings from climate data to audiovisual data. After that, George Xenakis introduced the key scientific concepts behind working with tree talkers. After lunch, we had a show and tell session where first, Mahmoud B. Elmokadem, Subhash Arockiadoss and Krishna Nama Manjunatha presented the progress on the hardware side of the prototype, and Luigi Marino introduced a detailed account of the lessons learned from designing the streamers for the forest. Next, we detail a bit more about the day and the key takeaways.

Quick introduction about StF, WP2, the hackathon

George and I gave a warm welcome to the participants and gave a short introduction to the project. We presented the vision and aim of the Sensing the Forest project, and in particular what we expect from Objective 2 and the hackathon. We also briefly mentioned the forthcoming participatory design of a tree talker prototype scheduled for February-April 2025. Then, we moved to Ireti’s talk.

Ireti Olowe’s talk: [Audio. Visual. Audiovisuals] Instruments for Sensing: The Common Denominator

Bio: Ireti Olowe’s research focuses on employing data as creative material, specifically related to audiovisual expression and performance. Audiovisuals represent a broad range of interdisciplinary practices where image, interwoven with sound are performed and projected through some form of creative endeavor. Through Creativity Support Tools, Ireti seeks to explore sound and its associated data as phenomena, facilitating meaningful outcomes that provide agency and opportunities for creativity. Ireti has led industry research projects in games, virtual and urban experience, Web3, Internet of Things, digital twins, and smart cities, contributing expertise in human-computer interaction and user experience. Currently, she is a research fellow at UAL’s Creative Computing Institute working on the AHRC-funded Transforming Collections discovery project for the Towards a National Collection program, where she focuses on user interfaces that enable humans, facilitated by machine learning, to interrogate and manage museum-collections-as-data.

Abstract: An Information Age that continuously evolves as it transitions into subsequent Industrial Revolutions, requires new instruments to explore knowledge derived from behavioral systems that conform them. Systems eg., natural, human, analog, and digital, that may differ in oddity, operation, osmosis, and output, however, find convergence in their extracted, distilled numerical and semantic forms. Either common denominator provides means to embed meaning and transform raw data extracted from systems and, in turn, behaviors that represent them into artistic material for exploring phenomena creatively through audio (sonification), visual (visualization), and audiovisual interpretation. This talk focuses on how data extracted from climate phenomena, specifically humidity, temperature, sap flow, and soil moisture can be employed by creative instruments to generate knowledge discovery and inspire exploration for storytelling and tacit understanding.

The talk was also open to attend online by Forest Research staff members and QMUL students from the QMUL’s MSc module Interactive Digital Multimedia Techniques. The talk was well-attended with 10-20 online attendees and the hackathon group onsite of 7 people. With a solid foundation in her PhD work Bountiful Data: Leveraging Multitrack Audio and Content-Based for Audiovisual Performance, Ireti presented different approaches that we can consider when mapping climate data to audio, visual, or audiovisual. Mapping was defined as *“using behaviour of one modality to control behaviour in another modality”. Ireti gave us a summary of mapping strategies and techniques. Ireti recommended to use of metaphors to create a narrative that others can understand, with a particular focus on the variables we want to measure, such as humidity, temperature, soil moisture and sap flow. Many considerations were raised, such as the environment as a system and the entanglements that exist, the open-ended nature of engaging with data, and factors that can influence such as time, space, and features. Also, she stressed aspects that need to be considered when designing for others with an emphasis on playfulness, interaction and discovery, as well as potential sources of inspiration, such as Scavengers Reign. Overall, the talk was enlightening and a food-for-thought for the entire hackathon.

WP2/Tree talkers

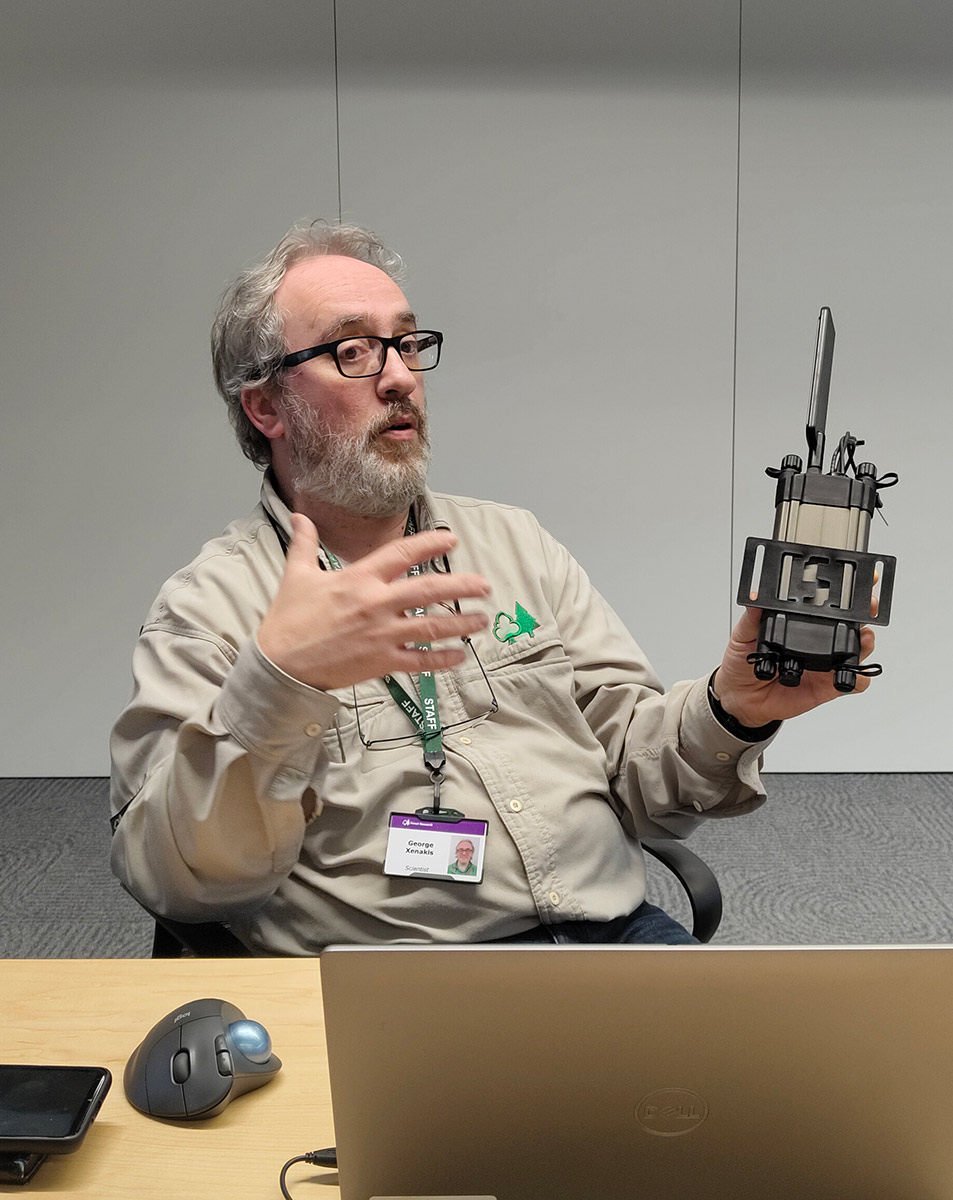

Georgios Xenakis, a co-investigator of Sensing the Forest who is the lead of the WP2’s vision, presented relevant concepts about stress in trees, and how trees can respond to stress in terms of what changes to their physiology and the use of resources. We realised that it is important to understand the different parts of a tree because by observing them, we can know if the tree is stressed or not. For example, trees have stomata, which are tiny pores on the underside of leaves that allow for the exchange of gases and water. When stomata close, there is stress.

Then he introduced us to the concept of sap flow, which refers to the water movement within a tree. This connects with the live part of the tree (sapwood) as opposed to the dead part of the tree (heartwood). Georgios works with tree talkers, which helps understand water movement and if the tree is stressed. The technique requires inserting two probes into the xylem tissue, and a heat pulse method determines the sap flow velocity by comparing the temperature of the heating probe with the reference probe. Positive values indicate upward sap flow while negative values indicate reverse sap flow.

Tree talkers measure the conductance and not the resistance of the sap flow. The higher the difference between the two probes, the higher the speed of the flow of water in the stem. Typically, fast sap flow occurs during the growing season, whereas slow sap flow occurs during dormancy in the winter. Sap flow can be affected by several factors, such as temperature, humidity, sunlight, and soil moisture. We are planning to explore these relationships as part of the project, which should be reflected in the prototype.

Another highlight is the unit of measurement of the tree talkers. The quantity of the water is measured in cubic metres (m3) captured as length (in meters) per width (in meters) per height (in meters).

Sap flow is often expressed as litres (L) per hour: cm3 (volume of sap) per cm2 (area of sapwood) per hour (time). This means that we need to know the area of the sapwood.

The last part of the presentation proposed some ideas and informative questions to develop the prototype. Informing people is the main goal of the prototype, and George envisions the use of clear concepts such as more water => happier tree and less water => sadder tree, where we can operate with the values of 1=tree happy and 0=tree is struggling. Connecting water with the flow should consider that there is a lag between the cause and the effect. Hence, granularity is important. This similarly happens with soil moisture and the sap flow. George proposes that perhaps a granularity of 10 minutes of data collection should suffice.

The talk concluded with a sonification that George created to showcase the energy balance (see below). George is using real data of net carbon capture from a mature Sitka spruce plantation as measured by scientific equipment at the Harwood long-term flux monitoring site. Monthly values of net carbon capture together with meteorological data were converted into music to make this composition. George is mapping the different values to different instruments. Reflecting on Ireti’s talk, we discussed that it would be useful for the listener to be able to mute/unmute the different instruments/tracks to understand better how each variable/instrument works so that the relationship among the different variables can be facilitated.

Show and tell

This session was meant to be for showing informal presentations of related projects/prototypes we have been working on, to get to know each others’ skills.

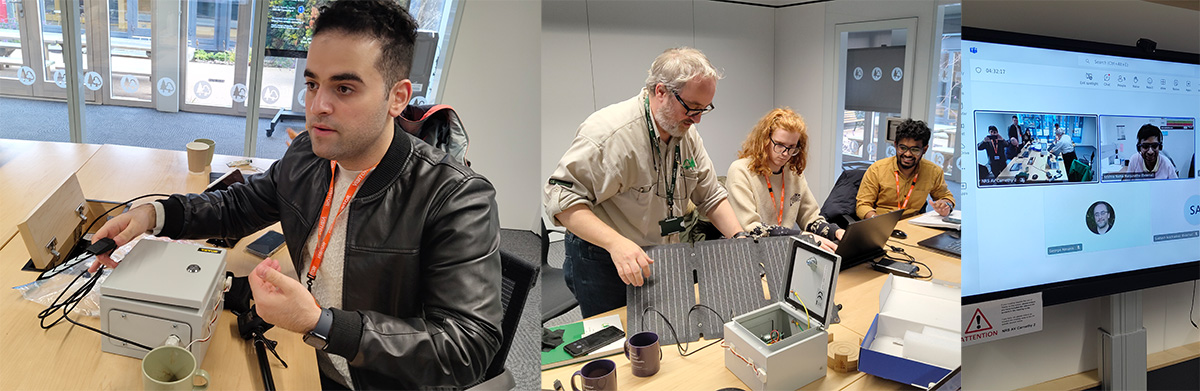

Mahmoud B. Elmokadem, Subhash Arockiadoss and Krishna Nama Manjunatha presented the progress on the hardware side of the prototype and Luigi Marino introduced a detailed account of the lessons learned from designing the streamers for the forest.

Mahmoud B. Elmokadem: the node

Mahmoud started summarising the progress so far achieved with the hardware prototype that under Krishna’s supervision, Mahmoud and Subhash have been working on.

The node prototype has the following features implemented:

- Simultaneous charging of power bank from solar cell while drawing the power from power bank to power R-Pi.

- Possibility to track and monitor power consumption of RPi with and without sensors.

- All parts are assembled in a small cute and robust metal enclosure that is waterproof.

- Ability to measure, record and display the readings of temperature, humidity, and soil moisture.

Mahmoud also discussed the ongoing work on:

- Improving the accuracy of the readings and sending JSON file data.

- Working on the assembly and fittings, which is giving some challenges but a few solutions are considered with the help from the Mechatronics workshop at DMU.

- 3D printing a few parts to help with holding the parts within the enclosure.

George recommends the team add a switch on/off to avoid the spikes of the sensors and to save battery. Choosing a sampling interval will be important. To make it more efficient, it is also recommended to turn off the visuals of the RPi, no desktop, no browser and just use the command line to reduce the resources. Given that there are different types of soils, we also discuss about calibration of the soil moisture sensor, which is expected to be done by the user before measuring a particular soil. We will need to make sure to add to the instructions how to calibrate the sensor, which typically will need a bucket with soil, water it, let it dry, and measure the voltage to be mapped. Finally, it is advised to use a precise clock for the timestamp because otherwise, the interpretation of the data can be misguiding.

Subhash Arockiadoss: DIY sap flow sensor

Under Krishna’s supervision and Mahmoud’s mentoring, Subhash has been also working on investigating comparing, selecting and analysing the system design of the sap flow sensor, to propose a potential solution for a DIY implementation. Subhash presented a very detailed analysis comparing three different commercial products and some suggestions on customising a commercial sensor from one of the companies. The presentation had well-presented technical block diagrams and schematics, that allowed us to understand how the scenario of converting from the analogue signal of the probes to the digital signal would work, as well as how the data processing of the digital value would be converted from the temperature calculation to the sap flow calculation.

This presentation gave us more evidence that we might build only one DIY sap flow sensor to demonstrate what we promised in the project, but it might not be economically feasible to scale it up to more units. George proposed that we might consider an alternative to the DIY sap flow sensor that should be easier to use and with an affordable price, which is the band dendrometer. A dendrometer is a sensor that measures the growth of trees, which can vary over the day, months and years. This created a nice discussion of whether a dendrometer would allow us to “sense the tree”. We agreed that we would like the users to experience the tree and the environment in terms of what happens if there are environmental changes (e.g. warmer/drier/wetter temperature) and how this can help the user start making connections with climate change.

Luigi Marino: the streamers

Luigi shared with the group his experience of building two DIY streamers for the forest without using mains. This has been (and still is) a difficult challenge because a) the streamers are on all the time (so not switching on/off the system is possible to save energy) and b) one of the streamers is under the canopy, which has a general lack of sunlight, especially since the days have become shorter in autumn, which affects the unit because it is based on solar-powered energy combined with a car battery.

Luigi has presented both the hardware and software of the two streamers. Giorgio, the streamer in the small meadow, has been presented as the successful proof of concept that the system works. Paula, the streamer under the canopy in the Willows Green trail, has been presented as the challenging case. For example, not only the lack of sun is an issue, but also the humidity, which affected the MEMs microphone becoming rusty after a few days, and this affected the sound quality of the soundscape.

The feedback from the hardware part was very useful. On the one hand, George mentioned that when the season changes, the inclination/angle of the solar panels needs to be increased to capture the lower sun. He also suggested the Photovoltaic Geographical Information System, which helps to plan what solar panels you might need depending on the time of the year and the location. We should also be careful when the car battery is too low because if you let the charge drop too low, your battery can become irreparably damaged. Another piece of advice from Mahmoud is to buy a fire-protected blanket to cover the plastic box that contains the battery to prevent any potential issues.

Next, Luigi presented the software in terms of how it works and what libraries it is using. Apart from the updated version that Luigi developed so that it would work with the latest OS version of Raspberry Pi, there are several libraries that are used related to audio features, modem features, and recording features, among others. For example, to make the recordings based on the astral time, the astral library is used. As final feedback, George mentioned that there is a lot of work in the streamers. Luigi is planning to polish the code for publication, as well as improve the quality of the recordings and the efficiency of the battery under the canopy.

Dinner

We concluded our first hackathon day by having dinner at Mowgli Street Food Edinburgh, where we celebrated a very productive first day. We also agreed that we would continue working as a team (without any subteams) on day 2, and outlined a plan for the day, which would be more focused on hands-on demonstrations, data, and mappings.

What’s next

Tomorrow we will have a more hands-on experience of learning how to install a tree talker and then discussing data and mappings as a team. We should have something visible/audible by 3pm to show to Ireti Olowe, who will act as an opponent of our prototype.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Forest Research Northern Research Station for hosting us during these two days and to the team members for all the nice contributions to the hackathon.